I'll leave for another time discussion of the changed experiences of listening to rather than reading a book. What I want to note now is a bit of appreciation I've gained for just how intriguing were times in which the American Founders lived--and how little most contemporary Americans probably really know of them.

For instance, I'd be interested in a poll that asked people to correctly determine what claim to fame made John Adams a shoe-in for the first Vice-President of the United States. I can say with some shame that I had no knowledge of Adams' meeting with the British Admiral Howe (or that Howe-the-Elder's [sic] younger brother was a general who commanded the British ground force before Cornwallis) that very nearly brought a peaceful end to the Revolution not one year after its inception; or of his work in France during the Revolution; or of the praise he received for securing two multi-million dollar Dutch loans, despite British threats against the Dutch navy; or that he served as the first American Ambassador to England, just a few months after the war ended.

Or that despite the historical attention paid to the animosity between Jefferson and Adams, until Adams became Vice-President, the two had been rather close friends. Jefferson and Adams had vacationed together while Adams was Ambassador to England and Jefferson to France. Abigail and Jefferson had a lengthy (if, toward the end, very terse) correspondence. Abigail had, while in England with John, cared for Jefferson's daughter for several months. And John Quincy Adams wrote of many a formative hour spent in the company of Thomas Jefferson, when both families resided in Paris.

No, the real hatred between revolutionaries was between Alexander Hamilton (Federalist) and Jefferson and James Madison (Republicans). I recommend the Adams and especially Washington biographies in large part because of the number of hilarious insults it unearths with respect to this particular hatred. For instance, in a letter to Washington after Jefferson had retired as Secretary of State and Hamilton remained Secretary of the Treasury, Jefferson (ever the xenophobe) writes of Hamilton:

"I will not suffer my retirement to be clouded by the slanders of a man whose history, from the moment at which history can stoop to notice him, is a tissue of machinations against the liberty of the country which has not only received and given him bread, but heaped its honors on his head."In another letter, this time to Madison, Jefferson writes of a speech Washington gave before leading American forces against the Whiskey Rebels. The speech contained "a parcel of shreds of stuff from Aesop's fables, and Tom Thumb," which sufficed to convince Jefferson that that speech had been written by Hamilton. Snap!

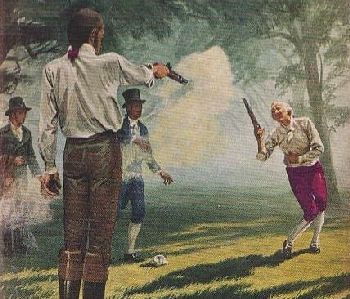

To really get a grip on that hatred, it's hard to forget that one of Jefferson's closest allies and the Vice-President of the United States killed Hamilton in a duel. I mean, he killed him! Now the story is shrouded in more than a little mystery and intrigue, but here's how I understand it, after having read a few historical accounts. By the beginning of the 19th century, death by pistol-duel had become a pretty uncommon way to die, given that the practice had devolved into a sort of gentleman's face-saving event. At this time, the order of operations began with one man taking the first shot, unencumbered by cross-fire from the second, since it was assumed by the second that the first would purposefully mis-aim and fire to the second shooter's right or left. Then, the second shooter would do the same. Each man, having defended his respective honor, then departs the field.

Of course, that's not how it went down in Burr v. Hamilton's torso. The story is that while Hamilton may have, indeed, intended to purposefully miss Burr, Hamilton nonetheless shot the branch immediately above Burr's head. According to Burr's supporters, the breach in protocol left Burr uncertain as to whether Hamilton had accidentally or intentionally mis-fired, and Burr unwilling to give Hamilton the opportunity to be more forthcoming in his intentions (the two used single-shot Wogdon pistols, as the flintlock revolver was not invented until 1814 or so), shot Hamilton in the abdomen, whereupon Hamilton promptly died 36 hours later.

Of course, that's not how it went down in Burr v. Hamilton's torso. The story is that while Hamilton may have, indeed, intended to purposefully miss Burr, Hamilton nonetheless shot the branch immediately above Burr's head. According to Burr's supporters, the breach in protocol left Burr uncertain as to whether Hamilton had accidentally or intentionally mis-fired, and Burr unwilling to give Hamilton the opportunity to be more forthcoming in his intentions (the two used single-shot Wogdon pistols, as the flintlock revolver was not invented until 1814 or so), shot Hamilton in the abdomen, whereupon Hamilton promptly died 36 hours later.Interesting, those lives and times. Reader, I entreat you to think upon just how much America has changed from then to now. From a time when the Vice-President could shoot the Secretary of the Treasury, to a time when the Vice-President can only shoot a lawyer. That's a long way, I know. The more amusing image, of course, is that of Joe Biden mortally wounding Tim Geithner. Now that, I should think, really would be a bfd.